Secrets of the deep unlocked on St Helena

Research undertaken each year on this remote island is vital for understanding one of the planet’s most mysterious creatures – and tracking climate change

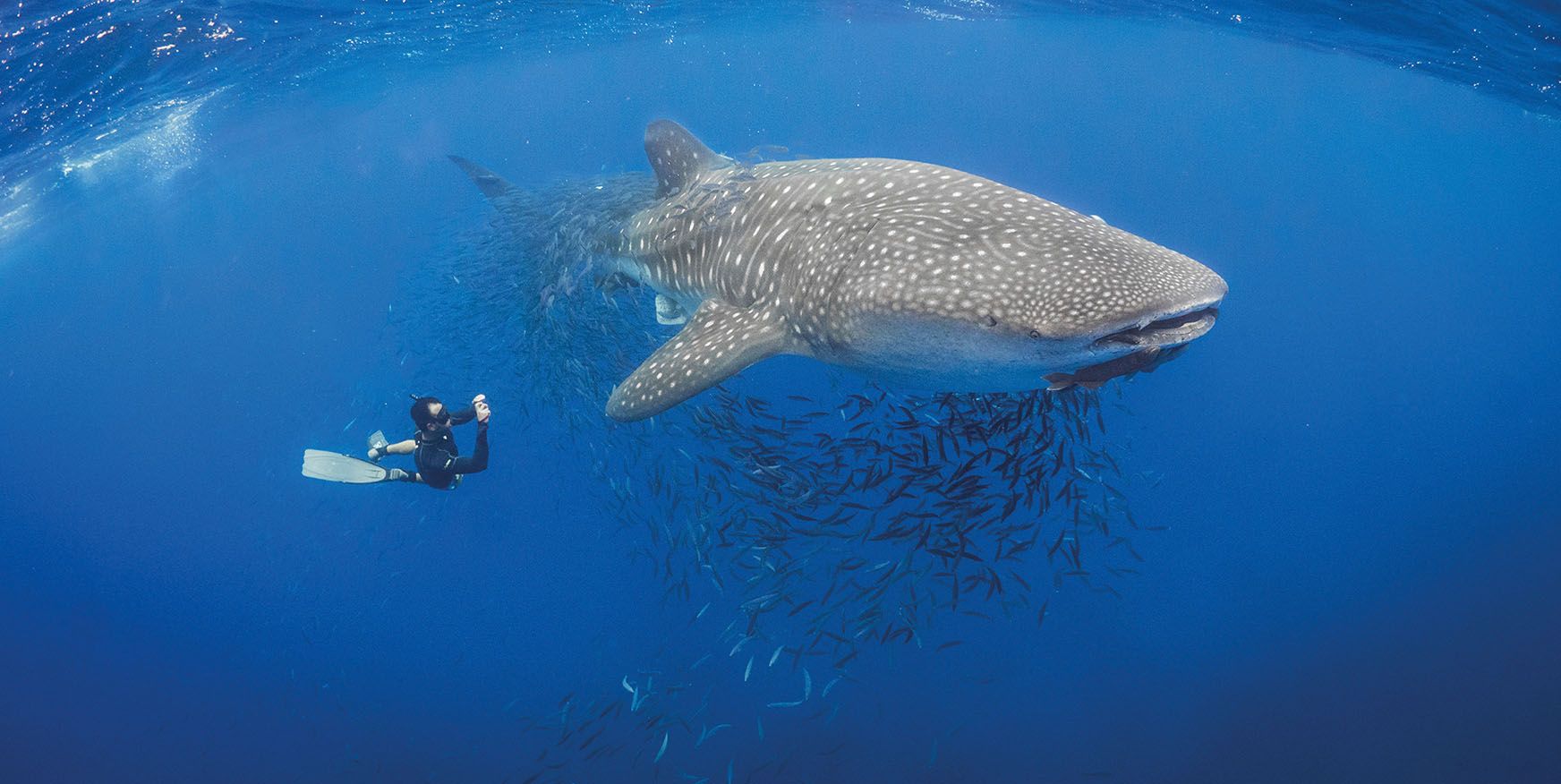

Whale shark season at St Helena Island officially began in December, with the sighting of this year’s first shark. Nearly 2,000 kilometres west of Africa, and with a population of just 4,439 inhabitants this mid-Atlantic island is one of the remotest places on the planet – and from December to March each year it boasts a whale shark population unlike any other. Their annual return to the island is of global significance and signals the potential for ground-breaking discoveries new to science.

Whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) are the largest fish on Earth and are listed as endangered on the IUCN Red List. Although they’re massive – measuring anything between 5 and 12 metres and weighing around 20.6 tonnes – they are mysterious creatures, which we still know very little about. For instance, we don’t know their exact migration habits, or how deep they dive (possibly up to 2,000 metres), or indeed how or where they mate.

As of January 2022, no successful mating attempt has ever been recorded. But this remote British overseas territory is the only place in the world where there is an almost 50:50 split of male and female adult whale sharks. So, could St Helena be a whale shark breeding ground? Could a successful mating attempt soon be recorded at the remote island? And where do St Helena’s whale sharks go for the rest of the year? Researchers based on the island are working to find out.

The Bone Shark Research Project

St Helena’s Bone Shark Research Project (BSRP) began in 2019 – “bone shark” is the local term for the whale shark. The programme is led by the three-person Saint Helena National Trust Marine Team, which is funded by the Blue Marine Foundation. They work alongside the St Helena Government Marine Section and collaborate with international whale shark experts to identify the most important questions and develop novel research to answer them.

While two to five weeks of research was undertaken annually by the government in previous years, the BSRP now takes place over four or five months, around January to May, once local fishers report the arrival of the sharks at St Helena. The significant increase in survey time since 2019 means enhanced data collection and increased probability of new discoveries. Last year the BSRP undertook 42 half-days at sea, resulting in 36 shark sightings and 58% of IDs being entirely new to the global database.

The team uses photo ID – capturing images of each shark’s unique pattern of white spots, which act like a fingerprint – and adds these to the global database Wildbook. This database makes it possible to track individual whale shark movements by showing the locations each shark has been recorded at and when. To date, 311 different sharks have been identified in St Helena’s waters that have never been recorded anywhere else in the world.

Although in its infancy, the BSRP has captured video footage of mass aggregations (over 70 animals) at St Helena. And it has used a National Geographic Remotely Operated (underwater) Vehicle to explore what factors might make St Helena an attractive gathering site. It has also trialled methods, such as faecal matter analysis, to ascertain inorganic material consumption and diet. Of course, the BSRP is also in the running to record the world’s first successful whale shark mating attempt. This year the project is partnering with the UK Government’s Blue Belt Programme and St Helena Government to use the global stereo-BRUVS programme to monitor whale sharks without human presence and at greater depths than ever.

Monitoring and management

St Helena itself measures just 47 square-miles (approx. 122 sq-km) but is surrounded by a Category VI (Sustainable Use) Marine Protected Area (MPA) nearly the size of France. The BSRP plays a critical role in monitoring the MPA and managing human/species interactions through engagement and education.

Neither SCUBA diving nor flash photography is allowed with whale sharks at St Helena, however swimming or snorkelling with the sharks is allowed – and this is of socio-economic importance to the island, as a beloved activity for locals and one of the island’s greatest tourism attractions. The BSRP says that long-term monitoring programmes for creatures like whale sharks – which encapsulate data about marine megafauna but also the microfauna and environmental factors affecting their wellbeing – are critical for developing robust management measures for the MPA and its wildlife. Conservation and management efforts of the BSRP have contributed to a government Marine Management Plan and a Code of Conduct for Swimming with Whale Sharks.

Climate change

“The distribution of whale sharks indicates the presence of plankton and the overall health of our oceans,” according to the World Wildlife Foundation. The 2020 BSRP recorded just 37 individual whale sharks, while 127 were recorded in the 2019 season – it also found that in 2020, the sharks were swimming deeper underwater than previously known. These findings may indicate changes in seawater temperatures and/or microfauna spawning times. Further BSRP research into these changes is important for whale shark research, but also feeds into global climate change data – data that is especially important as it comes from an otherwise underserved mid-Atlantic location.

The BSRP is also collecting data about microplastics and recording other marine sightings during surveys – last year the BSRP recorded the first leatherback turtle ever seen at St Helena), and studying other species encountered on surveys, such as hammerhead sharks, which are seen on approximately 70% of the 2020 boat surveys. Hammerheads listed as Critically Endangered, but it is not yet known what species of hammerhead inhabits St Helena’s waters; the BSRP hopes to find this out.

For further information:

www.sainthelena.gov.sh

www.bluemarinefoundation.com/projects/st-helena